Smallpox

Smallpox is a disfiguring and often-deadly disease caused by the variola virus. The pox part of smallpox is derived from the Latin word for ‘spotted’ and refers to the raised bumps that appear on the face and body of an infected person. There is no specific treatment for smallpox and the only effective way of preventing the disease is vaccination. As a result of vaccination, smallpox as a disease occurring in nature was officially eradicated in 1980. Vaccination against smallpox was then stopped until the threat of biological attack brought vaccination back to certain populations.

How can you get it?

Smallpox is transmitted through droplets in air from face-to-face contact, direct contact with infected bodily fluids or contaminated objects such as bedding. Insects or animals do not carry this virus. The most infectious period is while a person has the rash until the last scab falls off.

Symptoms

The pox part of smallpox is derived from the Latin word for “spotted” and refers to the raised bumps that appear on the face and body of an infected person. The incubation period is 7 to 17 days.

The signs and symptoms of smallpox may include:

- High fever

- General ill-feeling (malaise)

- Backache

- Rash

- Initial red spots that become raised bumps, pus-filled blisters and finally scab over in a few weeks

- Bumps and blisters start in the mouth and spread to cover the entire body from the head moving quickly down to the toes. All lesions are at the same stage of progression. Chickenpox looks roughly similar but the lesions are more superficial, vary with spots, bumps and blisters present at the same time in the same area over the body

Variola Major is the most severe and most common form of smallpox with a fatality rate of 30%. Variola Minor is the less severe and less common form of smallpox with a fatality rate less than 1%.

Complications include disfiguring scars where the blisters healed, skin infections, pneumonia, brain swelling and blindness

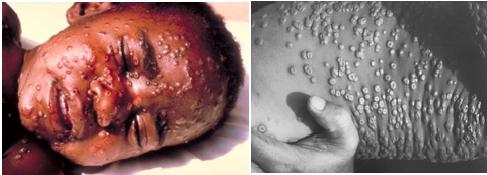

Pictures from the CDC are included below to illustrate the differences between smallpox lesions and the lesions of chickenpox:

Same stage of all the lesions as well as a depression in the middle of each lesion

Presence of red spots & blisters together

Prevention

Smallpox is a vaccine preventable disease. The vaccine does not actually contain the smallpox virus but a similar virus called “vaccinia”. The vaccination cannot give a person smallpox since the viruses are different. However, there are serious complications and contraindications associated with smallpox vaccination. See the Vaccinia pages for more information.

The vaccination process involves the use of a two-pronged needle that holds a droplet of vaccine. The needle pierces the skin several times to produce a sore and a few drops of blood indicate the skin was properly punctured. The vaccination results in a typical progression to a blister and then a scab as seen in this picture. A booster is needed every 10 years.These people should get the vaccine:Laboratory staff working with smallpox virusesMembers of the smallpox response teamsMilitary personnel directed to receive the vaccination

- If there is a known or suspected smallpox bioterrorism event anyone directly exposed to the smallpox virus should be vaccinated

- Some people are at risk of serious complications if they receive the vaccine. These include anyone with eczema, suppressed immune systems, pregnant, breastfeeding or with specific heart conditions

In addition to vaccination, you can help prevent the spread of smallpox by:

- Preventing contamination and performing decontamination of surfaces. Use disinfectants such as bleach and ammonia to clean contaminated surfaces.

- Using Droplet, Contact and Universal Precautions

- Assume patients with respiratory symptoms are contagious and provide masks for symptomatic patients.

- Limit the number of crew members having direct patient contact.

- Cover skin lesions to prevent aerosolization or contact.

- Hand hygiene (wash with soap and water or using an alcohol based hand rub)

- Personal protective equipment (PPE) (gloves, gowns, goggles, and respiratory protection).IAFF recommends P100 respirators for all patients with respiratory symptoms, such as cough.

- Proper handling and disposal of contaminated instruments/devices and clothing.

- Even those vaccinated against smallpox should use these precautions. The vaccination may offer some but not 100% protection against extremely high viral loads or against bioterrorism and “a genetically engineered virus.”

- Use respiratory hygiene/Cough etiquette

- Research has shown that airborne smallpox droplets may travel 6 feet or more from the source.Therefore, the following ambulance features should be used as available:

- Operate ambulance or vehicle ventilation systems in nonrecirculating mode and bring in as much outdoor air as possible.

- Operate rear exhaust fan during transport, if available; air should flow from the front of vehicle, over the patient, and out the rear exhaust fan.

- Use recirculating ventilation units with HEPA filters when available.

What should you do if you are exposed to the disease or get the disease?

- Notify your infection control officer.

- See a health care provider who can distinguish the skin lesions from chickenpox

There is no specific treatment for smallpox infection. If an infected person receives the smallpox vaccine within 4 days after exposure this may lessen the severity of the illness.