Infectious Disease

Infectious diseases are a health and safety concern for members of the fire service community. While on the job, IAFF members may be exposed to several potentially life-threatening communicable diseases including MRSA, HIV, and tuberculosis. The 2020 NFPA Injury Report found that there were over 20,900 exposures to communicable diseases during the reporting period. In the U.S., more than 25 states have passed legislation that designates certain infectious diseases as presumptive illnesses for fire fighters and EMS providers.

Infectious diseases, also known as communicable or contagious diseases, are illnesses caused by “harmful microorganisms, including bacteria, viruses, fungi and parasites.” (La Dou) Occupational infectious diseases are these same illnesses that result from a person’s exposure to these microorganisms while he or she is at work/on the job. Occupationally contracted contagious diseases are considered compensable through the workers’ compensation system, just like any other job-related disease.

While working, fire fighters are often exposed to many different kinds of people in many different, uncontrolled settings. They often respond to emergencies involving victims who have been injured and are actively bleeding. They often do not know the health status of their victims, including what sorts of infectious diseases they may have. These victims may require rescue from a difficult to access accident scene, such as a motor vehicle accident or poorly accessible building. There may be broken glass or other sharp objects at the scene that are poorly visualized, and the lighting at the scene may be minimal. In addition, if a victim is bleeding profusely, and needs to be extricated quickly to save his/her life, the emergency provider may act in haste, with disregard for his or her own safety.

Fire fighters also may be involved in emergency medical treatment at the scene, including intravenous line insertion and blood drawing, and during these procedures, may accidentally expose themselves to infectious disease from those they are trying to help. Exposures to blood, body fluids, open wounds, aerosols from coughing, sneezing, talking, and even intact skin can allow the microorganisms to enter the body and cause illness. All of these factors combine to place the fire fighter at increased risk of contracting a contagious bloodborne disease.

The Chain of Infection

Overview

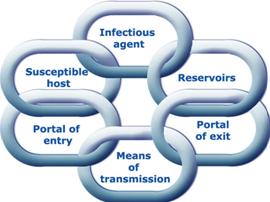

For an infection to occur, a certain sequence of events must take place. This sequence of events is often referred to as the chain of infection. This chain is made up of sections that link together to form the infectious process. The chain must include a:

- Pathogen

- Mode of Transmission

- Route of Exposure

- Susceptible Host (such as the human body)

What is a pathogen?The first link in the chain of infection is the pathogen. A pathogen is anything that causes a disease. Pathogens include:

- Bacterium – A group of microscopic organisms that are capable of reproducing on their own, causing human disease by direct invasion of body tissues. Bacteria often produce toxins that poison the cells they have invaded. Numerous bacteria also live in harmony with the body and are necessary for human existence, such as bacteria that aid in digestion in the gut. Important bacterial diseases include “strep” tonsillitis, pneumonia, and meningitis. (example: bacterial meningitis or strep throat)

- Virus – A group of microbes that are incapable of reproducing on their own, and must invade a host cell in order to use its genetic machinery for reproduction. Viruses are smaller than bacteria, and are responsible for the most common human diseases, the common cold and the “flu” (influenza). Viruses are also responsible for more serious diseases such as AIDS, hepatitis B, and hepatitis C. (example: hepatitis A, hepatitis B, and hepatitis C)

- Fungus – A single-celled or multicellular organism that can be true pathogens that cause infections in healthy persons or they can be opportunistic pathogens that cause infections only in immunocompromised persons. (example: athlete’s foot)

We come in contact with pathogens every day. Most of the time our body’s immune system destroys them before they can cause harm.

- We are considered Exposed when we have been in contact with a pathogen.

- We are considered Infected when a pathogen has entered the body and resulted in disease.

Whether an exposure results in infection depends on three factors:

- Dose – the amount of organisms that enter your body.

- Virulence – the strength of the organism.

- Host resistance – the ability of your immune system to fight infection.

What are the modes of transmission?

Exposure occurs through either direct or indirect contact.

- Direct transmission occurs when a pathogen (an agent that causes disease, esp. a living microorganism such as a bacterium or fungus) is transmitted directly from an infected individual to you. For example, you could become infected with HBV (Hepatitis B Virus) if you had an open wound that was exposed to a patient’s HBV infected blood.

- Indirect transmission occurs when an inanimate object serves as a temporary reservoir for the infectious agent. For example, you could become infected with HBV if you come in contact with equipment that has dried infectious blood on it.

It is important to note that many diseases do not manifest themselves immediately. Therefore, it can often be difficult to track the source of an exposure.

Many of the symptoms of some diseases can be quite similar to the flu. Therefore, if flu-like symptoms do not subside in a normal amount of time with normal treatment methods, you may need to have blood tests performed to rule out other possible causes.

What are the routes of exposure?

Pathogens can enter the body through four primary routes:

- Inhalation

- Contact with blood or other body fluids

- Ingestion

- Fecal-oral (ingestion of something that has been contaminated with the feces of an infected person)

- An intermediate carrier (vector such as a tick or another animal or soil)

What is a susceptible host?

A susceptible host is a person who is vulnerable to getting an infection. Certain groups of people are more vulnerable than other groups. For example, children, the elderly and immunocompromised (patients with weaker immune systems) patients are more vulnerable to getting infections than people who have a normal immune systems.